Oto Rimele’s paintings-objects that produce a material-free colour shadows are created in a long process in the studio. His watercolours, lined into series, are direct and quick responses to experience. As is governed by the old rules of the watercolour technique, the painter usually draws inspiration from the landscape, which is even recognizable in some paintings. Nevertheless, in principle, Mr Rimele’s watercolours are abstract. His perception of the landscape is frequently related to the horizon that appears to separate the earth from the sky and is especially exciting when viewed from the sea shore when the sea level and the sky are almost equal in colour. For these images, the painter often chooses distinctively elongated paper formats and presents the viewer with a thin, glowing white line that separates the sea (or the earth) from the sky.

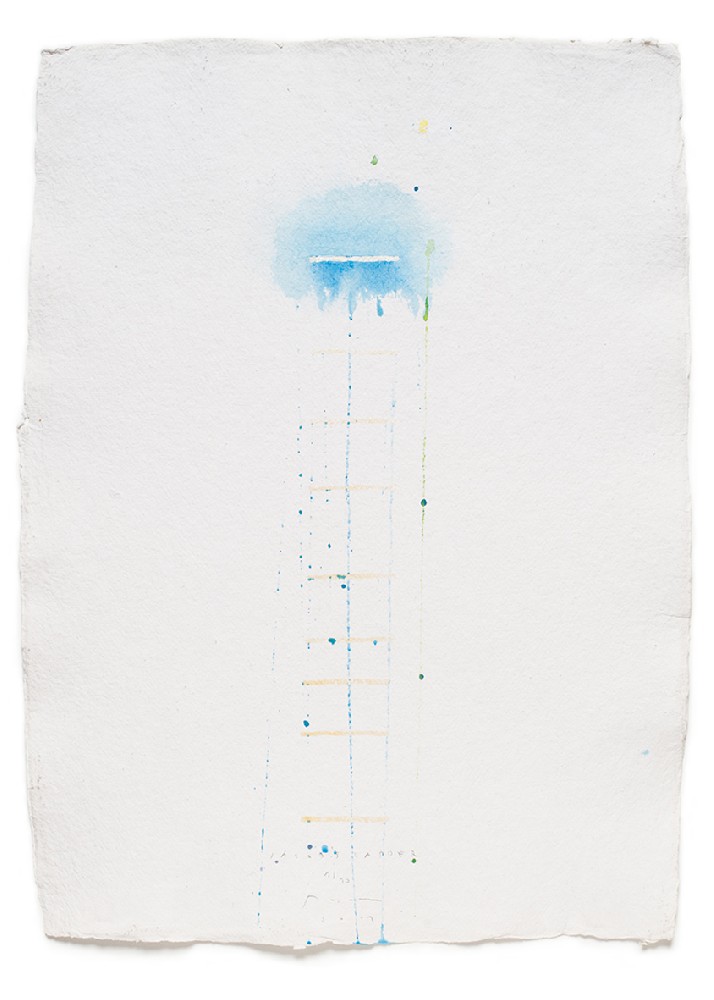

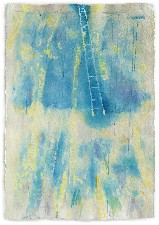

In 2019, Oto Rimele painted ten watercolours quite large in size (approx. 800 x 600 mm), in which the predominant motif of the horizon was replaced by the Jacob’s ladder scene. The relation between the earth and the sky changed. All the papers are positioned vertically; the lower part features the earth, which is depicted more or less explicitly, the main part is occupied by ladder rungs floating in the unidentifiable void, and the upper part depicts the sky. Thin droplets of paint fall from the celestial sphere down between the rungs; they can be understood as expressions of infinite emotions and suffering or as glittering rays from the beyond. The application of watercolour paint on the roughly-structured hand-made paper is typical of Oto Rimele’s work. The effect of transparency prevails, but a large part of the paper surface is also left uncovered. The glittering white rungs stand out. Rimele achieved the light radiation effect, which is one of the main areas of his research in fine arts. Parallel to the large watercolour series, the artist created ten small square shaped watercolours (approx. 100 x 100 mm) with the same content. Due to the changed format, the number of rungs is reduced from five or seven to three or four, and the watercolour as a whole is more abstract. The painter coloured the back page of the small watercolours in intense yellow. Owing to the manner in which the watercolours are attached to the wall in the exhibition area, the tiny paintings are surrounded by a gentle yellow shadow – Jacob’s ladder is floating in the gallery.

Both watercolour series can be interpreted in accordance with the story from The First Book of Moses (28, 10–21). The biblical Patriarch Jacob dreamt of a ladder reaching up to the sky with angels ascending and descending on it. At the top of the ladder stood the Lord, who promised to give Jacob the land he fell asleep on and predicted that his generation will expand and that he would never leave this land. When Jacob woke up, he recognized the land where he was sleeping as the house of God and the door to heaven. He turned the stone where he lay his head into an altar. The Jacob’s ladder motif was particularly popular in the Middle Ages when they understood the story as a metaphor for Paradise and the announcement of Jesus Christ’s Ascension. Most older depictions of Jacob’s ladder follow the story from the Old Testament quite faithfully, but sometimes the artists allowed themselves some creative freedom. In Dutch painting, for instance, the ladder is sometimes replaced by light rays or the angels ascend and descend without touching the rungs of the ladder.

Jacob’s ladder has always been understood as a bridge between the earthly life, where our experience resides, and the other life, which remains completely secret except for a few chosen ones who can perceive a certain reflection from the beyond, but this can only happen in certain states, for example, in one’s sleep. In the past, it was significant that the depictions of Jacob’s ladder clearly defined the earth and the sky. However, the modern man also identifies with the undefined top of the ladder, which may get completely lost in dizzy heights. The mysterious power of Jacob’s ladder lies in the message of the biblical metaphor; yet, should we follow the Slovenian philosopher Marko Uršič’s interpretation, art also possesses a cognitive tendency characteristic of scriptures. Oto Rimele marked the bottom centre of the large watercolours with the title (JACOB’S LADDER), the number in the series, the signature and year. All the pencil-made inscriptions are in line with the ladder’s compositional structure. It seems as if the written words also shape themselves into rungs, thus persuading us to think that the artist perceives his mission as a gruelling ascent towards the unknown and the unspeakable, towards the beyond.

Marjeta Ciglenečki

The cycle of ten watercolours was presented to the audience at the DDA Gallery, Pratt Institute Brooklyn, NY 11215. A printed document was also issued on this occasion. The expert text was contributed by dr. Marjeta Ciglenečki. The cycle The Jacob’s ladder (ten watercolors) is for sale as a whole.